The Origins of Lifespace Access

Lifespace Access, both the concept and company, have roots going back to historic and important times for Disability Rights and changing expectations for programs serving individuals with disabilities. The development of both the concept and the company also stems from a unique geographic setting.

In 1969 the California Legislature passed the Lanterman Mental Retardation Services Act. One of the key provisions of the Act was to create a system of regional centers to provide community-based services to support individuals who were in danger of being placed in state hospitals. In 1977 the Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act, the “Lanterman Act”, expanded Regional Center services to include other developmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism and other neurological disabling conditions. In addition to changing where these populations should be served, the Act mandated a fundamental change in how they were served. An Individualized Program Planning (IPP) process was to replace the traditional medical model, diagnosis-oriented, record

California State Capitol, Sacramento, CA

In Sonoma County the number of Individuals impacted by these new mandates was atypically large. The Sonoma Development Center was a large residential care facility operated by the California Department of Developmental Services. It represented a much older model for addressing the needs of individuals with severe and profound disabilities, with residents being placed there from throughout California. With the change in the state’s service model, there was an increasing need for alternative programs for school aged individuals being moved into community-based care homes and those leaving the Developmental Center to attend Severely Handicapped Special Day Classes that were being established on nearby school campuses. The Sonoma County Office of Education (SCOE) administered those classes.

Sonoma Development Center, Eldridge, CA

In 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Federal Developmentally Disabled Assistance and Bill of Rights Act. The law provided a federal definition for the relatively new term “developmental disabilities” which included mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism and dyslexia. It specified that these conditions originate prior to age 18, were expected to continue indefinitely, and constitute a substantial handicap. The Act stated that people with developmental disabilities have a right to appropriate treatment, services, and habilitation in the least restrictive setting that maximizes developmental potential.

President Gerald Ford signs Public Law 94-142, 1975

1975 also saw the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142), now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), signed into law. The purpose of the law was to assure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education which emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and to protect the rights of children with disabilities and their parents. The Individual Educational Plan (IEP) was introduced into school systems.

When I began working for the Sonoma County Office of Education (SCOE) as a School Psychologist in 1981 the legislative and geographical landscapes provided unique challenges and opportunities. By 1985 my role had evolved and included working to improve the instructional programs and outcomes for students with severe physical and developmental disabilities served in SCOE programs.

The physical and communicative limitations of these students represented major obstacles to providing meaningful instruction to address their unique needs. Our classroom programs began to use an emerging approach that utilized specialized equipment, most of which was homemade, to increase student access to learning and participation. Our efforts to enhance the instruction for these students began to pay off, and in 1987, SCOE opened the Adaptive Technology Center (ATC) to support them. With the help of two retired engineers the quality of our “homemade” hardware advanced. The ATC also supported a newly formed non-profit organization, Parents for Adaptive Learning Systems (PALS). This new approach, and an emerging curriculum model that incorporated adaptive technology, was successfully implemented in classrooms serving students from preschool to post-secondary ages.

Apple IIe and Radio Shack Engineer’s Notebook

In 1988, the approach we were using with our students was recognized by the Federal government of the United States. The Technology Related Assistance to Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1988 (Tech Act) officially introduced a new term, “assistive technology ”, and described an assistive technology device as “any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities.” The Tech Act also described an assistive technology service as “any service that directly assists an individual with a disability in selection, acquisition or use of an assistive

technology device.

In 1989, using a team of special education teachers and designated service providers (DIS) associated with our classes, our program and curriculum model were presented at the fifth annual CSUN Assistive Technology Conference. The reception of the team’s efforts at that, and other Special Education conferences, was encouraging

Cal State University Northridge (CSUN)

My experiences with this specialized population made it apparent that my professional training to be a school psychologist had not prepared me to provide meaningful evaluations of the abilities or educational needs of these students. By default, the evaluation needs of students in these programs were not addressed by the normative measures that underlie most psychometric assessment instruments. Discussions with other Special Education professionals showed that many shared my feeling about the inadequacy of existing assessment instruments and program planning processes for these students.

In 1990, Lifespace Access was formed to address this issue. Our transdisciplinary team drew on the collective experience of William B. Williams, MA, School Psychologist, Severely Handicapped Program Specialist and Assistive Technology Specialist; Gerald Stemach, MA, CCC-SP, Augmentative and Alternative Communication Specialist; Sheila Wolfe, MA, OTR, Occupational Therapist and Development Specialist; and Carol Stanger, MS, Bio-Medical Engineer.

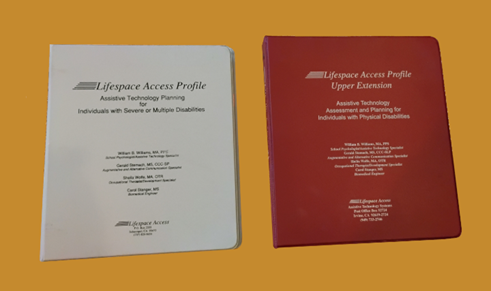

In 1993 that transdisciplinary team introduced the Lifespace Access Profile – Assistive Technology Planning for Individuals with Severe or Multiple Disabilities. Almost immediately there were requests for the Profile to be expanded to address the needs of individuals with physical disabilities and average or near average levels of cognitive functioning. This extension required further analysis of the use of assistive technology to facilitate access to academic activities and curriculum. The Lifespace Access Profile Upper Extension: Assistive Technology Assessment and Planning for Individuals with Physical Disabilities (LAP-UE) was published in 1994.

Lifespace Access Profile & Lifespace Access Profile-UE

By 1997 there was a growing cohort of Individuals with assistive technology integrated into their educational programs and lives. The Lifespace Access Profile LAP-Vocational Transition Planning for Assistive Device Users (LAP-VT) applied the Lifespace Access Profile framework to the creation of individualized plans for the transitioning of individuals with physical and neurodevelopmental disabilities into adult vocational programs.

The Lifespace Access Profile framework was utilized again in 2001 for the development of the Lifespace Access Profile-Autism Spectrum Disorder (LAP-ASD) to address the assessment and program planning needs for individuals at Levels 2 and 3 on the Autism Spectrum.

The IDEA requires the Individual be assessed in all areas related to the suspected disability, including, if appropriate, health, vision, hearing, social and emotional status, general intelligence, academic performance, communicative status, and motor abilities. The IDEA requires evaluation procedures use assessment tools and strategies that provide relevant information that directly assists persons in determining the educational needs of the child are provided. The evaluation must be sufficiently comprehensive to identify all of the child’s special education and related service needs, whether or not commonly linked to the disability category in which the child has been classified. The Lifespace Access Profiles help educators check all these boxes.

The Lifespace Access Profile model and its usefulness have been evaluated and cited in dozens of research papers and studies in fields ranging from Special Education and Assistive Technology to Occupational, Physical, and Speech Therapy, and Human Factors Engineering. Numerous school districts, educational and governmental organizations have incorporated the model into their assessment and individual program planning procedures.

The ongoing relevance and utility of the Lifespace Access Profiles are attributable to their solid conceptual foundations, the Learner Resources Model (LRM) and the Multidisciplinary Assessment and Planning Team.